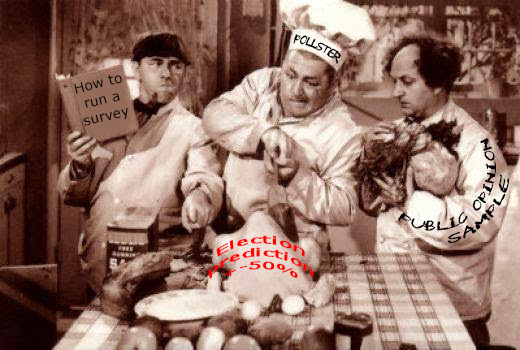

In our time and place, nothing lends more authority to a field than calling it a science. Polling has particularly benefited from the rigor implied by its association with the true science of statistics, and its jargon of sample sizes, margins of error and the like.

But faulty data defies the most stringent analysis, and that fact has undermined opinion surveys. The odds involved in a hundred coin flips are an iron law which experimentation will confirm. Should the flips yield a decidedly unlikely result, the coin itself comes under suspicion, not the math.

So should it be with polls. For the purpose of flipping, honest coins are identical, but people are unique in their combinations of characteristics and opinions. When virtually everyone had a phone and was willing to answer questions when called, collecting a representative sample of opinions was reasonably easy — pollsters had only to try enough numbers, and make minor adjustments to insure that those included in the survey mirrored the population in a few broad categories, such as age, sex, and party registration.

But changes in technology and in attitudes eroded the representative quality of respondents. The rise of cell phones made numbers more difficult to obtain, and users more hostile to unsolicited calls. Worse, general patience with questioning —especially the often long and tedious questioning common in political polling— diminished dramatically. Americans who once felt it their duty to cooperate with pollsters increasingly saw the calls as an imposition.

So long as those willing to respond still reflected the population as a whole, the falling response rate was only a concern, not a problem. But when the polls flopped in 2016, suspicion fell on the samples. Despite that awareness and the best efforts to rebalance, polls in 2020 were virtually worthless; a student of politics with a sense of voting history and an eye on the news could have predicted last month’s results better than the pollsters.

How bad were the polls? According to the Real Clear Politics compendium the presidential results missed by more than the margin of error in 24 out of 45 states (with no presidential polls reported in five states). In at least eight states, the polls were off by twice the margin of error or more. Dr. Joe Bentivegna went into the significance of such a wide miss in his recent op-ed at this site; as he demonstrates, the probability of such erroneous outcomes, if truly a matter of chance, is literally less than one in a million.

And if it were a matter of chance, the errors would be randomly distributed. Instead, the polls underestimated the Trump vote in 33 states, the Biden vote in just 11.

I don’t think that’s a matter of prejudice. Pollsters are in business to get the numbers right; if they don’t, they won’t stay in business long. Even if their goal were to aid Joe Biden, claiming that he was ahead where he wasn’t wouldn’t have helped him; anyone with campaign experience will tell you that in a tight race, complacency is more dangerous than discouragement.

If —as seems clear to me— the samples themselves are at fault, the question becomes what skewed them. The standard response is shy Trump voters: people reluctant to reveal that they planned to support the president. Clearly there was some of that, but I think the problem is more fundamental and intractable.

Consider one of the races where the polling was worst: U.S. Senate in Maine. All 14 public surveys, by eight different firms, showed Republican incumbent Susan Collins trailing; but on Election Day, she won by a comfortable 8.9%, a result well outside the margin of error for every one of those polls. I don’t believe there was any such thing as a shy Collins voter; the senator is a personable moderate, respected even by those who oppose her.

Nor does it seem likely that undecided voters broke late for Collins. An examination of the polling shows a static race for eight months, right up to the week of the election, with every survey predicting a level of support for the Democrat challenger higher than what she actually received.

Those who answer polls are cooperative people, and I would assert that cooperative people differ politically from the less cooperative. I don’t think anyone is surprised that conservatives are less inclined to obey mask mandates; should we be surprised that they feel less compelled to answer a telephonic interrogation? Educated professionals defer to institutions, and during this pandemic are more likely to be working from home, with time on their hands; wouldn’t they be more inclined to patience with a pollster than hard-pressed, blue collar laborers?

The media and the pollsters claim that better methodology will solve the problem, but I disagree: I think it is insoluble problem—and that’s no great matter. Polling is not essential to the electoral process. The focus on the horserace is fun for reporters and political junkies, but of no real value to voters trying to make up their minds.

Candidates generally work as hard as they are disposed to work, whether leading or trailing, and it can only be hoped that they base their positions on principle, not public surveys. Political professionals don’t need numbers to understand the electorate and sense the public pulse. If polling as we have known it is finished, the Republic and the campaign industry might both be better off.

![]()

Joe Markley is a former Connecticut state senator who was the GOP candidate for Lt Governor in 2018.