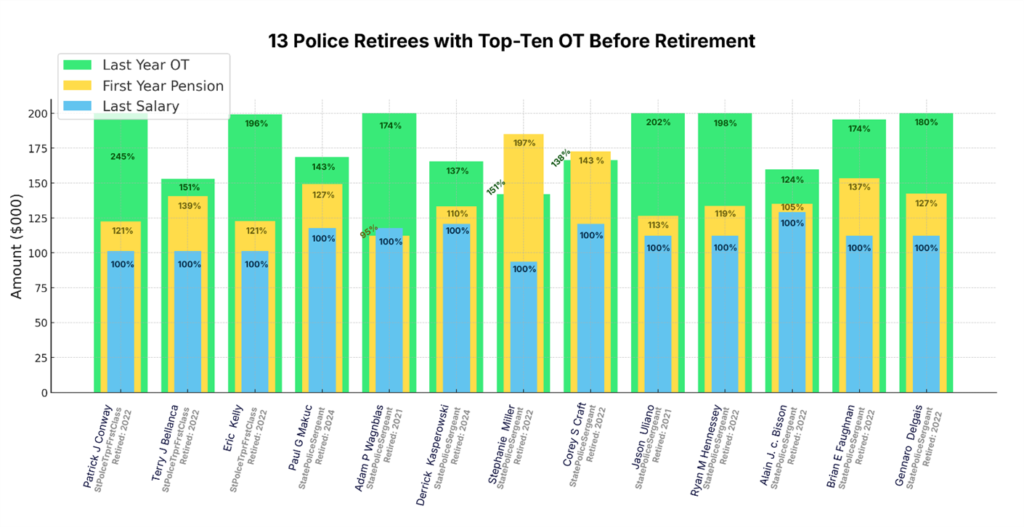

Connecticut state employees are retiring with pensions one-third higher than their final salaries. Yes, higher! Corrections workers with average final salaries of $75,000 have been retiring with pensions averaging $101,000, and state police officers with average ending salaries of $109,000 have retired with average pensions of $141,000.

How is this possible? Overtime spiking. Over 28,000 state workers have the right to include overtime in the calculation of their pension benefit. Unsurprisingly, many work long, long hours of overtime just before retirement. It is not to meet the manpower needs of their agencies, but rather to enrich themselves in retirement.

Don’t blame them; if you or I had their job under the contract negotiated by governors and union bosses, we would do the same. Indeed, most citizens appreciate the bravery and dedication of officers in these critical public safety jobs.

The problem is the contracts, which union bosses force upon weak-kneed governors interested primarily in their own re-election – Democrat governors desperate for union contributions and for union campaign “volunteers” and Republican governors (if ever again) fearful of triggering a deluge of union-funded negative ads.

Most of all, the practice persists because the public is unaware – and kept unaware by governors and even most members of the General Assembly who, otherwise, would have to answer embarrassing questions.

It is time to ask those questions, since Gov. Ned Lamont is negotiating with the unions, whose wage contract expired last June and whose benefit contract, including pension calculation methods, expires in about a year and a half.

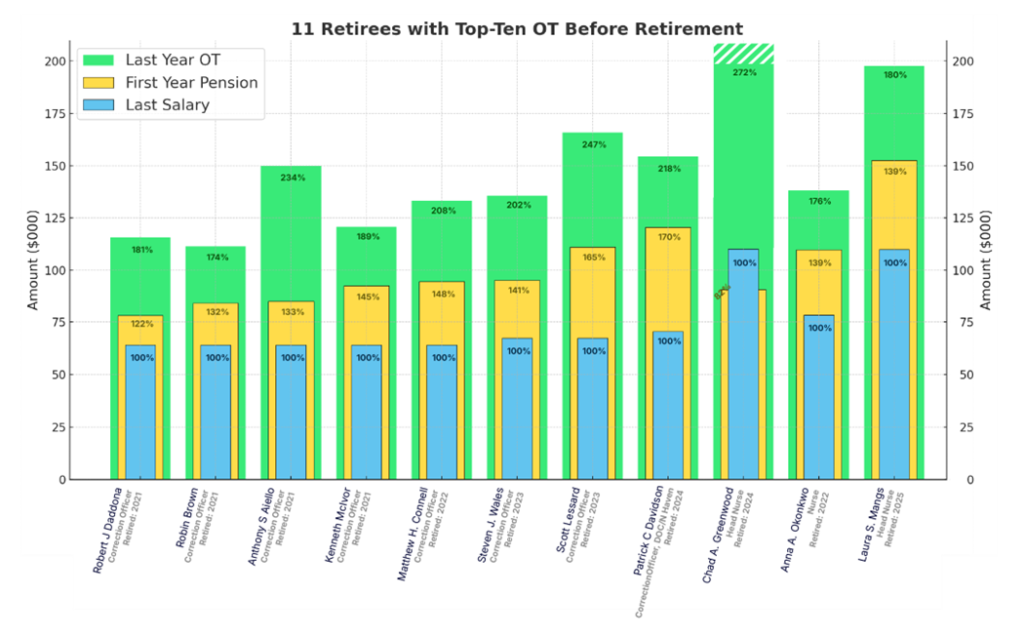

Recently The Townsend Group, which I head, was mandated by Yankee Institute and Nutmeg Research to conduct two studies of overtime (OT) spiking among Corrections workers and the State Police, using data from the Open CT database maintained by the State Comptroller. The eye-popping pension numbers cited above are the averages of employees who retired from the two agencies over the last five fiscal years, specifically 24 employees from a group of 61 constituting the 10 highest OT- earners in each of the last five fiscal years (61 rather than the potential 100 because some repeated).

These highest-OT earners are not bad apples. Almost all employees across both agencies OT-spike.

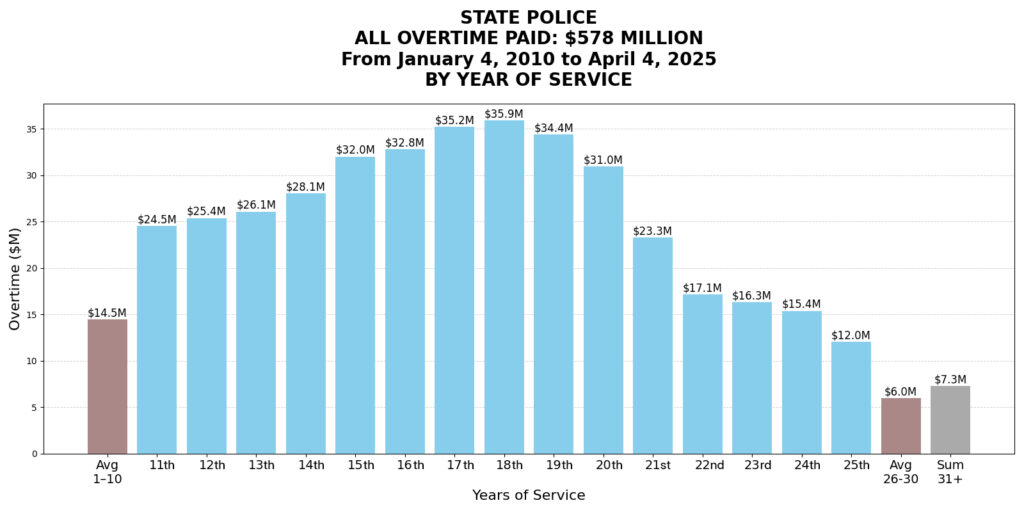

How did we determine this? For the State Police, we gathered the total overtime earnings of all State Police officers (and staff) for the last 15 years. It totaled $578 million. State police become eligible to retire in their 20th year of service (YOS) (with no early retirement option).

We rearranged this data by YOS, from the 1st to the 30th. Most of the overtime pay – about $390 million, or two-thirds of the total – was concentrated in half the period, the 15 YOS from the 11th to the 25th. In turn, we looked at the YOS immediately before retirement eligibility and found that State Police earned $106 million, or about 30% of the $390 million, in their 17th, 18th and 19th YOS. Since their pensions are based upon their three highest years’ earnings, this confirms workforce-wide OT spiking.

We conducted a slightly different analysis of Corrections workers with the same result.

OT spiking has devastating impact. In fiscal 2025, the state paid out $387 million in overtime pay, of which about $179 million, or almost half, went to employees of these two uniformed services agencies. Possible solutions or reforms are obvious: hire more officers and/or assign overtime evenly. If, as is claimed, this would make hiring more difficult, offer hiring bonuses, surely an equally effective and vastly less expensive option.

Overtime expense would plummet.

Yet, the payroll cost is less costly than the impact of OT spiking on pension expense. Take the example of the 11 high-OT-earning Corrections workers. Let’s assume, conservatively, that they received average annual pay increases of 2% over their 20 years on the job and will received 2% average annual cost-of-living increases in their pension benefit.

Over the next 20 years, their $101,000 beginning pension will grow to $150,000 in the 20th year and produce an aggregate of $2.45 million in pension benefits. With the same 2% increase assumption applied going backward, their starting salary 20 years ago was $51,500 before reaching $75,000 just before retirement producing aggregate salary over 20 years of $1.25 million. They will earn about twice as much in their first 20 years of retirement as in 20 years on the job.

Former Democrat governor Dannel Malloy ended OT spiking for all hires after 2017. He also imposed three annual wage freezes. In over six years in office, Ned Lamont has done the opposite: he has continued to indulge OT spiking by more senior employees resulting in these outrageous pensions, and he has awarded six consecutive annual pay raises cumulating to a 33% increase (vs. 23% in the private sector). Lamont’s gravy train for state employees continues to roll down the track.

![]()

Red Jahncke is a nationally recognized columnist, who writes about politics and policy. His columns appear in numerous national publications, such as The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, USA Today, The Hill, Issues & Insights and National Review as well as many Connecticut newspapers.