Governor Lamont unveiled his proposed Connecticut Comeback budget last week. A comeback is unlikely given the long-festering problem of overgenerous and woefully underfunded compensation for privileged state employees.

Politicians in Hartford consider this problem untouchable and intractable. They won’t even identify the problem by name, instead, referring to it as the state’s “structural” or “fixed cost” problem.

It is anything but fixed, because it is consuming more of the budget every year – about one-third of the $23 billion budget for next fiscal year ending on June 30, 2022.

For over a decade, state employee compensation has exceeded compensation in Connecticut’s private sector by about 40 percent, the biggest gap in the nation.

The consequence is that the State Employee Retirement Fund (SERF) is drastically underfunded. It is difficult to fund such wildly overgenerous benefits, especially since the state didn’t even start to fund them until years after beginning to award them.

What now is an ongoing gravy train for state employees is ultimately a train wreck for them and the state. There are only three ways to avoid the wreck: (1) massive tax increases and/or service cuts, a disastrous option (2) significant cuts in state employee benefits and/or (3) a federal bailout.

Sure enough, taxes are going up. Services are being squeezed. Yet, the gravy train rolls along. A major federal bailout is already in hand. A much larger one seems at hand. It may pay off the problem.

Absent Uncle Sam, the state’s fiscal woes are playing out within tight constraints of automatic fiscal controls instituted in the 2017 “bipartisan budget.”

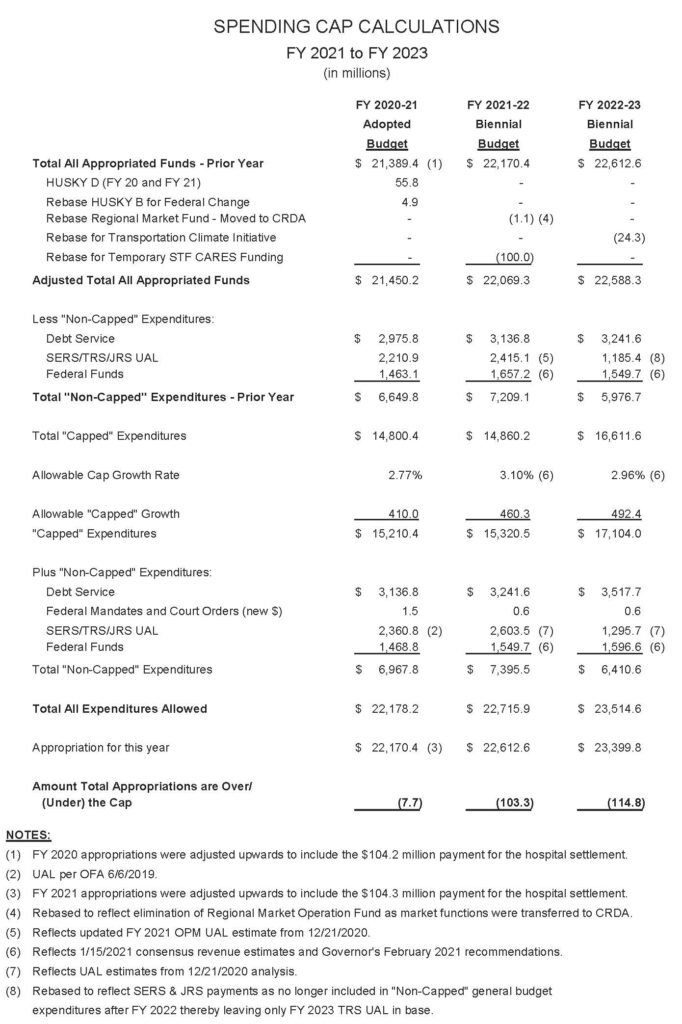

The “spending cap” limits growth in most state spending to the greater of inflation rate or growth in personal income in Connecticut, resulting in a 3 percent annual cap in Lamont’s budget. The cap’s rationale is simple and prudent: don’t spend more than the state economy can support and its citizens can afford.

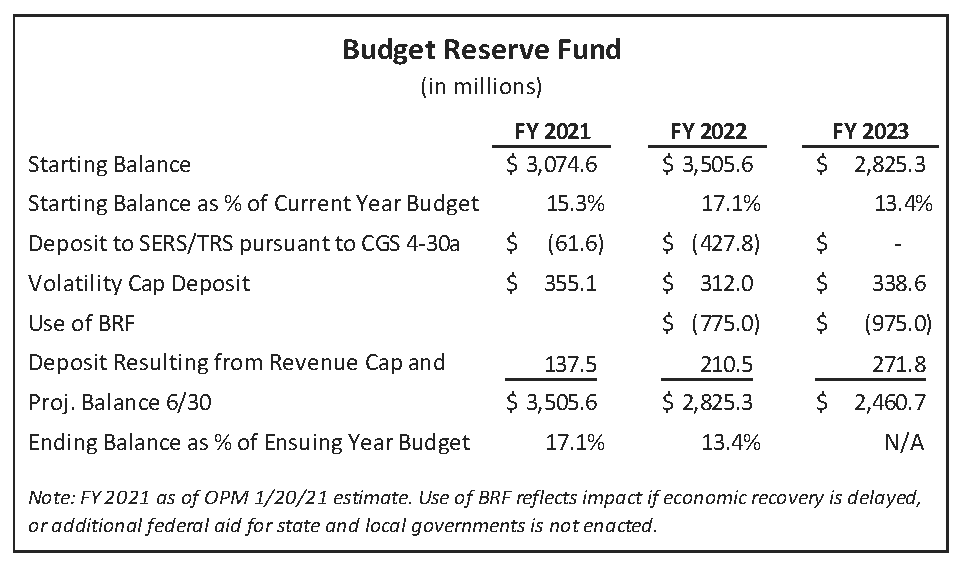

The “volatility cap” applies to income tax revenue from investment income, which gyrates with the stock market. Any such tax revenue over $3.115 billion (adjusted for personal income growth) must be deposited into the BRF. The idea is to save some of the gushing tax revenue from wealthy taxpayers during bull markets (the last four years) and save it for the lean years of a bear market. Lamont’s budget anticipates over $300 million in annual deposits into the BRF in fiscal 2021 through fiscal 2023.

The “revenue cap” sends funds to the BRF — one percent of revenue, or more than $200 million, in fiscal 2022.

No surprise, funds have, and continue to, pile up in the BRF, which brings us to another unnamed cap: the BRF is capped at 15 percent of the budget. Overages go into SERF and/or the Teachers Retirement Fund (TRF). This year’s overage is projected at a whopping $427 million.

This is a good thing and a bad thing – good because both SERF and TRF are drastically underfunded, recently as the result of both Lamont and his predecessor, Dannel Malloy, reducing state contributions to SERF with the approval of union leaders.

It is a bad thing when you remember that SERF pays dramatically overgenerous retirement benefits. Why not reduce the benefits to national average levels? That would improve the funding of SERF in a much fairer way.

There’s little fairness between state employees and the private sector workers. State employees have enjoyed a decade-long no-layoff guarantee, while hundreds of thousands of private sector workers have lost jobs, first following the financial crisis, and, now, during the shutdown.

State employees, in contrast, have received two 3.5 percent pay raises plus two 2 percent “step increases” in the last two years for a combined compound 11.3 percent pay raise.

To bring it full circle, when a huge hunk of the budget (state employee pay) increases 11.3 percent and the spending cap limits overall budget growth to only 3 percent, that means most of the rest of state spending must be reduced. State employee pay is squeezing out state services and eroding the safety net.

Yet even as state employees make out like bandits, their union leaders are screaming bloody murder, because Lamont’s budget doesn’t include any more pay raises.

Union members should worry more about their retirement benefits. For the first five years through July 2022, the state contribution to SERF is exempt from the spending cap; thereafter, it isn’t. Moreover, Lamont is requesting another $100 million reduction in the state’s contribution to SERF, proposing to “extend SERS amortization transition by 3 years.”

If union leaders agree, SERF will suffer; if they don’t, the squeeze on state services will worsen.

Either way, there is little prospect of a Connecticut Comeback until union members agree to renegotiate their pay and benefits. With over 100,000 active and retired state employees, modest individual concessions would generate a substantial amount in aggregate.

![]()

Red Jahncke is a nationally recognized columnist, who writes about politics and policy. His columns appear in numerous national publications, such as The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, USA Today, The Hill, Issues & Insights and National Review as well as many Connecticut newspapers.