President Biden and House Speaker McCarthy delayed their meeting on the debt ceiling from Friday to Tuesday. Maybe there’s progress as aides “negotiate.” Yet, the debt ceiling crisis is but a symptom of a much more consequential debt crisis in the U.S.

It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that Biden’s massive spending imperils the nation, risking an eventual ultimate default, not simply a temporary immediately-curable default. The debt ceiling has served a valuable function in forcing the nation to confront its unsustainable spending habit and its mountain of accumulated debt.

Very much sooner than expected, we will arrive at the ‘X Date,’ the day on which the Treasury runs out of money to pay Uncle Sam’s bills. According to the most recent Daily Treasury Statement, there was only $143 billion in Uncle Sam’s cash account, less than half of April’s modest peak of $316 billion reached on anemic tax receipts. Treasury Secretary Yellen badly misjudged the ‘X Date.’

Ill-advised by Yellen or acting on his own accord, President Biden refused, for three months, to negotiate with House Speaker McCarthy… until last week. For the good of the nation, McCarthy should not yield on House Republicans’ demands for spending cuts.

While deficits are not new under Biden, they are of distinctly un-survivable magnitude. Moreover, Biden is particularly blameworthy, since it is plainly obvious that his spending is “the straw” that is breaking the camel’s back through record inflation and widening deficits. Previous profligacy may have been as reprehensible, but it did not break the nation.

Last Wednesday’s Monthly Treasury Statement showed a seven-month deficit of $925 billion. In fiscal 2022, the seven-month deficit was only $393 billion, yet it was followed by $1.0 trillion over the next five months. So, the full-year deficit in fiscal 2023 is almost certain to surpass $2.0 trillion.

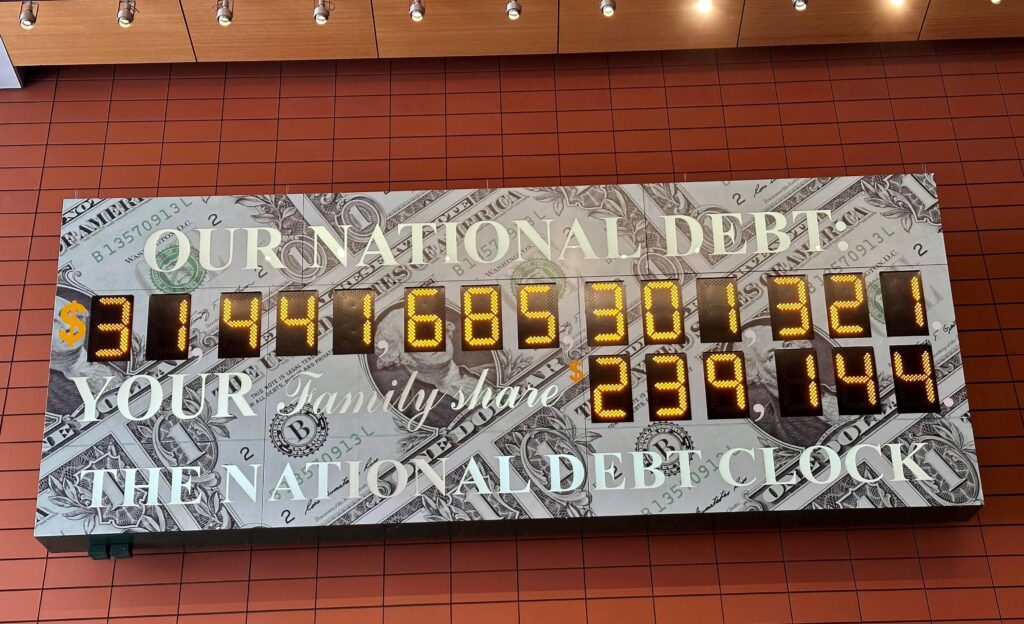

Deficits require additional borrowing in equal amount. A $2.0 trillion deficit necessitates $2.0 trillion of new debt, or yet another $1.5 trillion to be raised by September 30th on top of the $1/2 trillion that had already been borrowed this fiscal year by the time the national debt hit the current $31.4 trillion ceiling in January.

Stunning enough numbers, but what really makes the debt crisis manifest and urgent is skyrocketing interest on the debt. Net interest (gross interest less interest on the $6 trillion of Treasuries held in government trust accounts) increased a whopping $107 billion, or 40%, in the first seven months of fiscal 2023.

Inevitably, it will continue to increase, as outstanding Treasuries with lower interest rates mature and are replaced by new ones with the much higher interest rates produced by the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes over the last year. Another $107 billion increase over the next five months would increase full-year net interest expense by 45% to about $690 billion compared to $475 billion last year.

Interest of $690 billion on the $28 trillion of net national debt implies an average embedded interest rate on total outstanding Treasuries of about 2.5% ($690 billion divided by $2,800 billion) at the end of fiscal 2023. That is far below interest rates today (about 5.25% on short-term Treasury bills and more than 3.5% on long-term Treasury bonds).

Soon, interest expense will exceed every item in the budget except Social Security.

Treasury interest rates drive all interest rates, so a massive increase in interest cost is being experienced across the broad economy, making recession quite possible, if not probable.

While, in a recession, interest rates would come down, federal interest expense would still rise. Tax receipts would decline, forcing Uncle Sam to borrow much more to replace the lost tax revenue. During the Great Recession, tax receipts fell 25% from 2008 to 2009. So, even at lower interest rates, the federal government’s interest expense would remain high – and debt would surge to new heights.

The upshot of all this is that, without cutting spending, the likely scenarios lead to continued unaffordable levels of interest expense and an even higher mountain of debt.

Yet some people in Washington still resist. They claim that not raising the debt ceiling amounts somehow to reneging on financial commitments already made.

In truth, a debt ceiling increase is needed to fund past commitments, if, and only if, those past commitments were not funded when made. That is the problem in Washington: ever more unfunded spending. We need to fund commitments when made.

Biden has demanded a “clean” debt ceiling raise, yet, using new debt to fund Biden’s past deficit spending would just encourage him to engage in even more of the deficit spending that has led to our current perilous position and that, sooner than later, will lead to fundamental default, not temporary immediately-curable default. It is imperative to couple spending cuts with raising the debt ceiling.

![]()

Red Jahncke is a nationally recognized columnist, who writes about politics and policy. His columns appear in numerous national publications, such as The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, USA Today, The Hill, Issues & Insights and National Review as well as many Connecticut newspapers.