Has anyone noticed that the president has proposed increasing federal spending by nearly $1 trillion a year, while promising that 98% of Americans will pay nothing for it? The very idea would have seemed mad to every previous generation of Americans. Today it is considered conventional.

President Biden’s plans have been rightly criticized for the incontinence of the spending and the perversity of the taxes. Much of the spending is designed to exploit the pandemic crisis by transforming emergency income support into permanent middle-class entitlements for toddler care, higher education, medical services and much else. Other spending is called “infrastructure” but includes a list of progressive wants having nothing to do with capital investment. The tax increases—supposedly confined to the 2% with household incomes of $400,000 or more, but heavily weighted against capital investment—would seriously damage the economy and raise radically less revenue than claimed.

But set aside these problems and take the Biden plans as advertised, as a tremendous expansion of government paid for by a select few taxpayers plus lots of new borrowing. This is the apotheosis of a political transformation that began insensibly in the 1970s and has triumphed with barely a quiver of recognition, much less debate. It may be called the borrowed-benefits syndrome.

From the founding through 1969, the federal government followed a balanced-budget policy, not perfectly but with impressive consistency. Regular operations were covered by current taxes and tariffs. Borrowing was reserved for wars, economic depressions and other emergencies, investments in territory and transportation projects. The debts were paid down through subsequent budget surpluses and economic growth.

From 1970 onward, the country shifted to a budget-deficit policy—spending more than current revenue as a matter of routine, at first a little and then going big, through years of peace and prosperity as well as of war and crisis. Deficits had averaged 3% of spending in 1950-69, a period that included two wars, a pandemic and two serious recessions.

Deficits then grew to 10% of spending in the 1970s and 18% in the 1980s. The U.S. borrowed for 22% of spending in 2019, a growth year that would have called for a budget surplus under the old regime. The deficit ballooned to nearly half of spending during the 2020 pandemic, setting the stage for another ratcheting up of regular annual deficits under the Biden plans.

Many explanations have been adduced for the shift, such as the triumph of Keynesian economics and its techniques for fine-tuning aggregate demand. But the growth of deficit spending has hardly been fine-tuning, and has been practiced energetically by non-Keynesians such as Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump.

The best explanation is populist rather than academic: the shift in federal expenditures toward mass consumption. In 1970, about 36% of federal spending, net of interest payments, was benefits to individuals—Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid (new programs at the time), unemployment compensation, means-tested welfare benefits. Benefits spending then grew mightily, roughly in tandem with deficit spending, and is now about 76% of spending, heading briskly toward 80%. Most of this spending has been placed on autopilot and is exempt from occasional spending-reduction initiatives and government closures.

The shriveling share of spending on traditional government—defense, courts and law enforcement, parks and infrastructure, basic research—has remained subject to congressional appropriations. The Biden plans, while lacking in many details, would continue this profound change, with well over half the spending devoted to individual benefits.

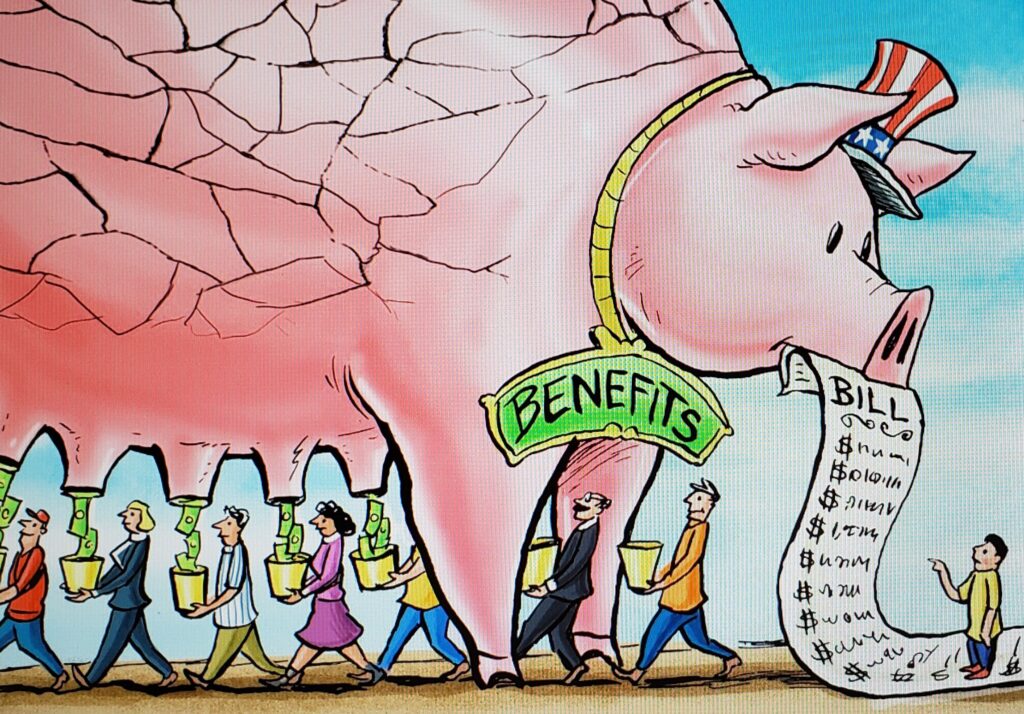

Politicians and citizens have gradually discovered a powerful new principle of political economy: The government provides large numbers of voters with immediate personal benefits that greatly exceed what it charges in taxes, billing the difference to future generations. This principle is the driving force of the Biden plans, which would be financed mainly by new borrowing, not taxes.

The principle is less salient in other advanced democracies because they raise healthy revenue from broad-based and often regressive levies on consumption, such as value-added taxes. The U.S., by contrast, has long depended on a highly progressive income tax that is complex and wasteful and produces relatively little revenue. The American tax system is increasingly an adjunct of borrowed-benefits policy—a means of distributing benefits rather than a means of paying for them. The conversion of the IRS to a social welfare agency would continue apace under the Biden plans with their profusion of targeted tax credits for families and green energy.

The borrowed-benefits policy deserves to be called a syndrome for two reasons. First, personal benefits, however much needed or described as “investments” by proponents, will not generate the future economic growth needed to pay down the debts incurred to finance them. Budgeting consumption spending according to imagined futures of trouble-free prosperity, rather than current revenues, is the real political legacy of Keynesianism. This technique is on display in the Biden administration’s rosy long-term economic projections for its spending plans.

Second, whatever the future may hold, the provision of borrowed benefits is deeply corrupting of democracy. It absolves citizens of recognizing their dependence on one another and politicians of accountability for managing the conflicts and constraints of today’s society. Instead, it encourages the fantasy that there are Croesuses in our midst whose “fair share” will pay for the benefits government wants to give us. This, too, is a central element of the Biden plans.

I have no solution for borrowed-benefits syndrome, which has dissolved the consensus that the welfare state is something citizens should be willing to pay for. I can, however, objurgate the politicians who have built their careers on propagating the syndrome far and wide, now with unprecedented aggressiveness in the Biden administration and Congress.

![]()

Mr. DeMuth is a distinguished fellow at the Hudson Institute. This article draws on his essay “The Rise and Rise of Deficit Government,” published this week at Law & Liberty.