President Biden traveled to Tulsa, Okla., Tuesday to mark the 100th anniversary of a race riot that destroyed a prosperous black community and is estimated to have left hundreds of people dead. The trip recalls President Obama’s 2015 trip to Selma, Ala., where police had beaten and tear-gassed peaceful civil-rights protesters 50 years earlier.

These historical milestones are certainly worthy of commemoration. Properly understood, they demonstrate how much racial progress has been made in this country in a relatively short time. Yet for progressives and their friends in the media, the events are also an opportunity to push for racial preferences and bigger government. The goal is to link today’s racial disparities to past wrongs and to play down or ignore the far more significant role that contemporary black behavior plays in social inequality.

When a National Public Radio reporter asked George Patrick Evans, Selma’s mayor, how events of 50 years ago fit into the “current conversation about race relations,” he balked at the question. “I’m not sure how it fits,” Mr. Evans, who is black, replied. “We have a lot more crime going on in 2015 all over this country than we had in 1965. Segregation existed but we didn’t have the crime.” Asked about the city’s high black unemployment rate, he still refused to racialize the issue: “Well, from the standpoint of jobs, we have lots of jobs. It’s just that a lot of people do not have the skill level to man these jobs. And that’s the biggest problem we have.”

In the run-up to Mr. Biden’s Tuesday address, the White House announced several new initiatives to “combat housing discrimination” and increase the amount of federal contracting with minority-owned small businesses. Putting aside the dubious legality of race-based government assistance, it’s worth noting that the black residents of Tulsa 100 years ago didn’t wait around for the federal government to come to their rescue. Within two decades of the riots, homes and churches had been rebuilt, and black-owned businesses again anchored the community.

READ MORE UPWARD MOBILITY

- Correcting 1619’s Falsehoods About the American Founding May 25, 2021

- Shrinking Blue States Have ‘Defund the Police’ to Blame May 18, 2021

- Classroom Chaos in the Name of Racial Equity Is a Bad Lesson Plan May 11, 2021

- Teachers Unions’ Covid Cop-Outs Are a Winning Issue for GOP May 4, 2021

- Race Relations in America Are Better Than Ever April 27, 2021

The political left is much more interested in black suffering than in black accomplishment, but black history is about more than victimization at the hands of whites. It’s also about what blacks have achieved notwithstanding that victimization. And in the first half of the 20th century, long before an expanded welfare state supposedly came to the rescue, blacks accomplished quite a lot. Incomes rose, poverty fell dramatically, and education gaps narrowed. Blacks entered the skilled professions—medicine, law, accounting, engineering, social work—at faster rates in the years preceding the 1960s civil-rights legislation than they did in the years afterward. Among racial and ethnic groups rising from similar circumstances, historians have described the rapidity of these gains as unprecedented.

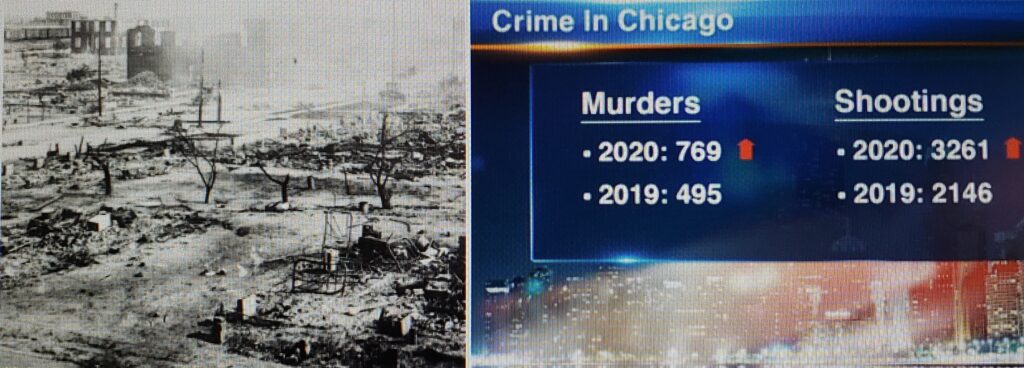

Black Tulsa residents of a century ago would also be shocked to learn that it is no longer racist white vigilantes but black criminals who pose the bigger threat to safety in black communities. Liberals blame today’s disproportionately high black criminality on the “legacy” of slavery and Jim Crow. But violent crime among blacks declined in the 1940s, then dropped even further in the 1950s, while remaining relatively stable among whites. In other words, blacks living during Jim Crow segregation, and much closer to the era of slavery, experienced significantly lower rates of violent crime and incarceration both in absolute terms and relative to whites.

The Biden administration would much rather discuss white criminal behavior in Tulsa 100 years ago than black criminal behavior in Chicago, Baltimore or St. Louis today. Likewise in his Selma address, Mr. Obama invoked high-profile police shootings, “unfair sentencing” and “voter suppression,” giving the impression that little had changed in the past 50 years, his own election and re-election notwithstanding. Liberals focus on this history of black suffering rather than success because it helps Democrats get elected and activists raise money. What’s less clear is how any of this helps the black underclass improve its situation.

This country’s racist past should never be forgotten or sugarcoated, but neither should it be used as a blanket explanation for present disparities. History teaches us that the progress of blacks and other minorities in the U.S. is not conditioned on racial tolerance. Asian-Americans are one of any number of groups that have faced racism and mob violence. One of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history targeted Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles, and Japanese-Americans were put in internment camps during World War II. Today, both groups outperform whites academically and economically and have for decades.

The left’s focus on the past behavior of whites, while ignoring the present behavior of blacks, might offer some people catharsis, and it might help groups like the NAACP or Black Lives Matter stay relevant. But where is the evidence that such an approach facilitates black upward mobility?

![]()

Jason Riley is an opinion columnist at The Wall Street Journal, where his column, Upward Mobility, has run since 2016. He is also a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and provides television commentary for various news outlets.

Mr. Riley, a 2018 Bradley Prize recipient, is the author of four books: “Let Them In: The Case for Open Borders” (2008); “Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to Succeed” (2014); “False Black Power?” (2017); and “Maverick: A Biography of Thomas Sowell” (2021).

Mr. Riley joined the paper in 1994 as a copy reader on the national news desk in New York. He moved to the editorial page in 1995, was named a senior editorial page writer in 2000, and became a member of the Editorial Board in 2005. He joined the Manhattan Institute in 2015.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Mr. Riley earned a bachelor's degree in English from the State University of New York at Buffalo.